In 1988, the Dolphins went 6-10. That was the only sub-.500 season the Don Shula/Dan Marino Dolphins ever had.

You probably won’t be shocked to learn that those Dolphins finished dead last in rushing yards and first in passing yards. After all, Miami finished first in pass attempts, and the team ranked 2nd in NY/A; meanwhile, the Dolphins ranked last in rushing attempts, and 23rd in yards per carry. The presence of Marino, a bad running game centered around Lorenzo Hampton and Troy Stradford, and a 6-10 record all paved the way for the 1st/last split.

In 2005, the Cardinals went 5-11, and also ranked 1st in passing yards and last in rushing yards. That team’s running game was terrible: Marcel Shipp and J.J. Arrington were the backs, and the team ranked last in yards per carry *and* rushing attempts (and rushing TDs), as Arizona finished 190 rushing yards behind every other team. But with Kurt Warner at the helm, a bad record, and that running game, Arizona finished 50 passes (including sacks) more than than any other team, and 327 more yards.

That doesn’t sound so weird, does it? But since 1970, those are the only teams to rank 1st in passing yards and last in rushing yards (seven others raked 1st/2nd and last/2nd to last). And only three teams have done the reverse, finishing first in rushing yards and last in passing yards.

The first, unsurprisingly, was the O.J. Simpson-led Buffalo Bills in 1973 during his historic campaign. Buffalo went 9-5 and finished first in YPC and 2nd in attempts, as Simpson had a 332/2003/6.0 stat line, while Jim Braxton (108/494/4.6) and Larry Watkins (98/414/4.2) produced solid numbers in support. Joe Ferguson was not very good at quarterback: Buffalo ranked last in pass attempts, 3rd-to-last in NY/A, and therefore last in passing yards (and TDs).

The presence of the 2003 Ravens in this group is not going to surprise any folks, either. The 10-6 Ravens had a great defense and a fantastic running game led by Jamal Lewis, who rushed for over 2,000 yards. Baltimore finished 1st in rushing attempts and 3rd in yards per carry, with Lewis doing most of the heavy lifting there. With Kyle Boller and Anthony Wright, the passing attack was pretty bad: it ranked 27th in NY/A and 32nd in attempts, so the last-place ranking in passing yards makes sense.

The third team is one most of you could probably guess: it’s the 2006 Michael Vick-led Atlanta Falcons. Atlanta finished 1st in rushing attempts *and* 1st in yards per carry, joining the famous 1978 Patriots as the only teams since the merger to pull off that feat. The Falcons rushed for 2,939 yards, the most by any team since 1984. The passing game led by Vick was not very good: Atlanta ranked 29th in NY/A, and since it ranked 32nd in attempts, it ranked last in passing yards.

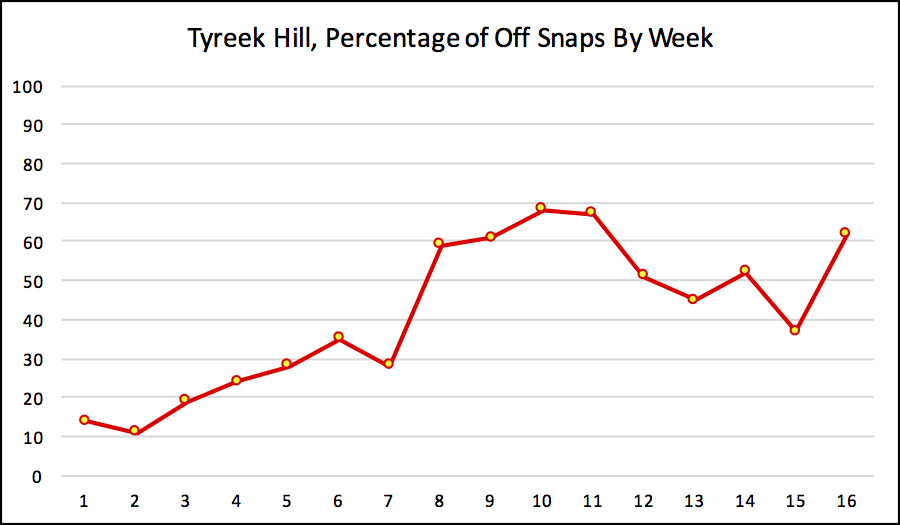

So why bring up those teams today? The 2016 Bills rank 2nd to last in pass attempts (by 1, to Miami) and 2nd in rushing attempts (Dallas), in a very 1973 Bills-like fashion. Buffalo easily leads the league in yards per carry (5.3), although right now the Cowboys (thanks to quantity) are only half a yard per game behind the Bills. LeSean McCoy is averaging 5.2 yards per carry, Mike Gillislee is at 5.8, and Tyrod Taylor is at 6.4; that group is powering an insanely efficient running game.

The passing game, meanwhile, is nearly as bad as the running game is good. That’s mainly because of a drop in yards per completion (from 8th last year to 25th in 2016). Taylor averaged 7.10 ANY/A this year and 5.73 this year; Buffalo ranks in the bottom 5 of the league in NY/A, so given the 31st-place ranking in attempts, it’s not too shocking that the Bills are last in passing yards (though the 49ers are less than 50 yards ahead of them).

As a result, the Bills look a lot like the ’73 Bills, and those two teams could make up half of the franchises since 1970 to rank last in passing yards and first in rushing yards.