Tis better to be with Gronk than without.

played for the New England Patriots from 2010 to 2018. It was one of the wildest and most celebrated rides in NFL history. But today I want to

build on the great work done by Adam Harstad and analyze Gronk’s career through the lens of how

Tom Brady fared — with and without Gronk. For defining what is included in my data set, please jump to the end of this post to see how Gronk games and non-Gronk games are defined.

I am going to not going to spend much time discussing Gronk’s first and last seasons, for two reasons. In 2010, rookie Gronk was not yet Gronk(TM); he also didn’t miss any games. And 2018 Gronk was BrokenGronk; outside of 2010 and 2018, he was pretty much always a dominant force when healthy.

So let’s focus on the prime 7 years of Gronk’s career. In 2011, 2014, and 2015, Gronkowski was almost always healthy. There was only one missed game of note there, and it was one where Brady and the entire Patriots team struggled. In those three seasons, Gronkowski was a unanimous first-team All-Pro selection each season among major voting publications.

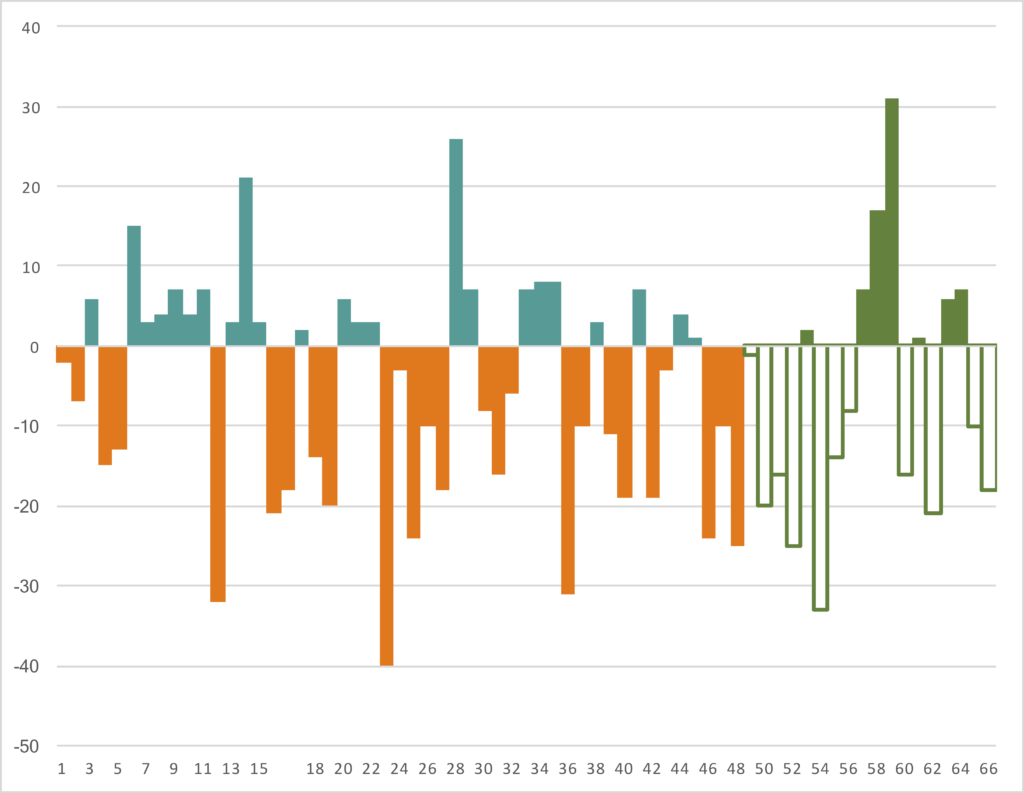

So, for WOWY purposes — that is, With Or Without You — the seasons we have to analyze for Gronkowski and Brady are 2012, 2013, 2016, and 2017. And the results are staggering in each year.

2012

The Patriots had 10 Gronk games and 8 non-Gronk games this season, which ended in a loss without Gronk to the Ravens in the AFC Championship Game. The stats:

- In the Gronk games, New England had a 0.700 winning percentage, averaged 35.8 (!) points per game, picked up 28.4 first downs and 16.4 passing first downs per game, and the passing offense averaged 7.73 Adjusted Net Yards per Attempt (ANY/A).

- In the non-Gronk games, New England had a 0.750 winning percentage, averaged 31.6 points per game, picked up 26.5 first downs and 15.8 passing first downs per game, and averaged 6.84 ANY/A.

Notably, that’s a difference of 4.2 points per game and 0.89 ANY/A per game without Gronk. And while the record was slightly worse, it’s worth noting that the three losses came by a combined four points.

2013

The Patriots had 7 Gronk games and 11 non-Gronk games this season, which ended in a loss without Gronk in the AFCCG to the Broncos. The stats:

- In the Gronk games, New England had a 0.714 winning percentage, averaged 32.0 points per game (and allowed 27.1 PPG), picked up 26.6 first downs and 16.3 passing first downs per game, and averaged 6.98 ANY/A.

- In the non-Gronk games, New England had a 0.727 winning percentage, averaged 25.4 points per game (and allowed 17.8 PPG), picked up 21.3 first downs and 12.3 passing first downs per game, and averaged 5.64 ANY/A.

The offense nearly fell apart without Gronk, dropping 6.6 points per game and gaining 5.3 fewer first downs. The passing offense declined by 1.34 ANY/A. And while I presume this is mostly (all?) due to randomess, this begins a trend of New England allowing significantly fewer points in non-Gronk games. Which is just weird.

2016

The Patriots had 5 Gronk games and 10 non-Gronk games this season — which was perhaps Brady’s best season outside of ’07. New England won the Super Bowl without Gronkowski. The stats:

- In the Gronk games, the Patriots posted a 4-1 record , averaged 32.0 points per game (and allowed 20.4 PPG), picked up 23.6 first downs and 13.8 passing first downs, and had a ridiculous 9.93 ANY/A average.

- In the non-Gronk games, the Patriots went 1o-0, averaged 30.4 points per game (and allowed 14.8 PPG), picked up 24.0 first downs and 14.9 passing first downs, and averaged 7.67 ANY/A.

It’s hard to argue with 10-0, and the team gained more first downs without Gronk… but the record was driven in large part by that defense, too. The Patriots averaged 1.6 more points per game with Gronk and 2.26 ANY/A per game with Gronk. In the 5 Gronk games, Brady’s stat line was just ridiculous, and the offense scored 20 touchdowns and had just 18 punts and one interception. That was, of course, an unsustainable pace, but it just highlights how dominant Brady and Gronk were in ’16; in the 10 non-Gronk games, the offense had 34 touchdowns and 47 punts. In these 5 games, Gronkowski caught 24 passes for 19 first downs, 529 yards and 3 touchdowns.

2017

The Patriots had 16 Gronk games and 3 non-Gronk games this season, which ended with a loss in the Super Bowl to the Eagles (but don’t blame the Patriots passing attack or Gronkowski, who had 116 yards and 2 touchdowns). The stats:

- In the Gronk games, the Patriots had a 0.813 winning percentage, averaged 30.4 points per game, picked up 25.8 first downs and 15.7 passing first downs, and averaged 8.22 ANY/A.

- In the non-Gronk games, the Patriots went 2-1, averaged 21.0 points per game, picked up 19.7 first downs and 13.3 passing first downs, and averaged 5.81 ANY/A.

That sounds like a huge drop — 9.4 points per game and 2.42 ANY/A — but the sample size is small. Brady played poorly in the two regular season non-Gronk games, an upset loss to Miami and a narrow win over Tampa Bay. Those were two of his worst games of the season, which probably wasn’t just a coincidence. I don’t want to make much out of a 3-game sample size, but putting aside the magnitude, the direction is consistent with other years.

Gronk WOWY Stats

Here are the full stats for Brady and the Patriots offense in each season, in both Gronk games (top rows) and non-Gronk games (bottom rows).

What Is A Gronk Game and What is Not A Gronk Game?

Finally, let me explain how I identified what is a Gronk game and what is not a Gronk game. Let’s work in reverse order:

- 2018: Gronk missed the games in weeks 8, 10, and 11 due to ankle and back injuries. While he was not necessarily his former self, he played in at least 67% of the snaps in every other game this season.

- 2017: Gronk missed 3 games here. He missed a game on a short week against the Bucs due to a thigh injury, was suspended for the second Dolphins game, and suffered a concussion in the first half against the Jaguars in the AFC Championship Game. He finished that game with just 1 target and 26 snaps, representing 41% of the team’s snaps. I am counting this as NOT a Gronk game (which the Patriots won). Note that in the regular season finale against the Jets, Gronk played most of the game (68% snaps) but functioned solely as a blocker: he did not record a single target. That still counts as a Gronk game, as it was more importantly for the Patriots offense, a Bryce Petty game.

- 2016: Gronk missed the first two games of the season with a hamstring injury, and played just 11 snaps (blocking on 10 of them) in the week 3 game against Houston. However, I am going to exclude all of the first four games of the 2016 season for New England, since Brady was suspended; those games are eliminated from this study and don’t count as a Gronk game or a non-Gronk game, since we are analyzing Brady’s WOWY stats. Then in week 12 against the Jets, Gronk suffered a season-ending back injury and played just 7 snaps. New England won, 22-17; this game is counting as NOT a Gronk game. So games 5 through 9 are the only Gronk games this year.

- 2015: Gronkowski missed one game (against the Eagles) due to a knee injury.

- 2014: Gronkowski began the year missing the preseason as he recovered from a torn ACL/MCL (more on this below); he wound up playing between 40 and 45% of the Patriots offensive snaps the first two weeks, where New England went 2-0. I am counting these games as Gronk games (he had 17 combined targets), but just wanted to note the injury. Gronkowski sat out the week 17 game, which would normally mean that’s a non-Gronk game. But because the Patriots had clinched the #1 seed before the week 17 game and Brady only played for the first half, so I am excluding that game as a non-Gronk game, too. That is the fifth and final game in this study I am eliminating entirely (along with the four suspension games for Brady).

- 2013: Gronkowski suffered a season-ending knee injury on a hit by T.J. Ward early in the 3rd quarter of a week 14 game against the Browns. Since Gronk played 49% of the snaps and made it into the third quarter, I will still count this as a Gronk game (as opposed to the Jaguars AFCCG).

- 2012: Gronk broke his forearm late in a win over the Colts in week 11; that game counts as a Gronk game. However, he barely played (31% of snaps) in his return, a tune-up, week 17 game to get ready for the playoffs, and then re-injured his arm seven snaps into the team’s first playoff game. He would miss the rest of the season. Both of those final two games are being counted as non-Gronk games. Therefore, the first 10 games of ’12 were Gronk games, and the last 8 games were non-Gronk games.

- 2011: No missed games.

- 2010: No missed games.

As always, please leave your thoughts in the comments.