Super Bowl LII. Nine seconds left, New England down by eight. Tom Brady had already thrown for 505 yards, but the Patriots still needed another 51 yards from him to have a chance to extend the game. Brady launches a prayer to Rob Gronkowski, who …

The Final play of the 2017 NFL Season. RT @TheRenderNFL: Tom Brady hail mary incomplete, Philadelphia Eagles win the 2018 Super Bowl #SBLII #SuperBowl pic.twitter.com/oE99C671Vw

— PHSports LiveScores (@LiveScoresPH) February 5, 2018

… nearly comes down with it in the end zone. Had the Hail Mary been completed, Brady would have thrown for 556 yards, setting a new single-game passing yardage record. The current record, as trivia experts know, is 554 passing yards, set by Norm Van Brocklin way back in 1951.

Eight years ago, I first wrote about how Van Brocklin held the record for most passing yards in a single game. I’ll be reprinting and updating that post today.

Let’s begin with the obvious: Van Brocklin is a Hall of Famer and all-time great quarterback who, at his very best, produced some of the most efficient and valuable seasons in NFL history. He should be on most top-20 quarterback lists, and his net yards per pass attempt — one of the most basic but important measures of quarterback play — is the best of all time.

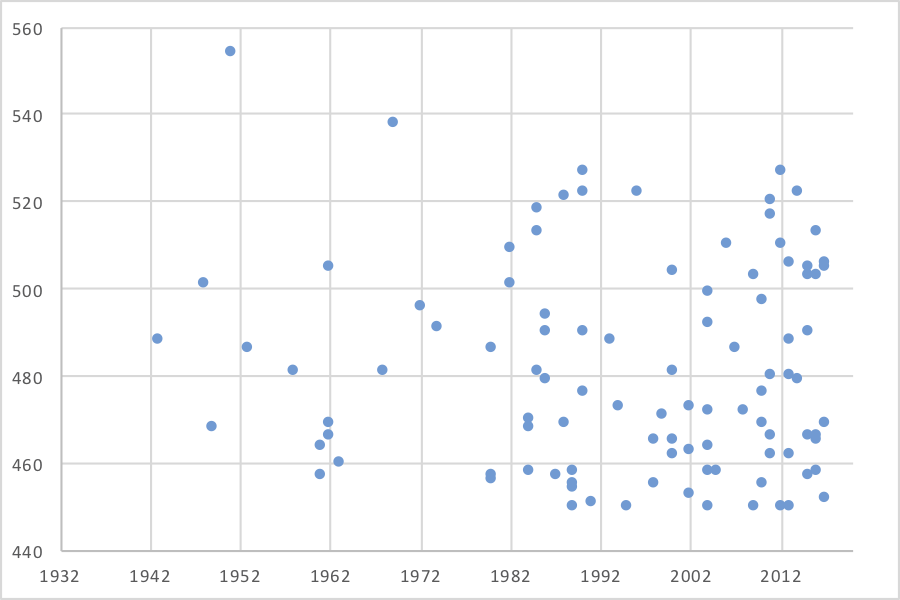

On the other hand, he set the record in 1951. How the heck did that happen? Below, I have plotted all games where a team has passed for at least 450 gross yards (that is, without deduction for sacks). As you can see, the dot at (1951, 554) is a pretty large outlier:

High passing games weren’t unheard of in the ’40s and ’50s, but they’re certainly more common now. And while the league has obviously shifted more from the running game to the passing game since Van Brocklin’s era, there is another reason to think his mark would have been broken by now: there are way more games than there used to be. Since 2002, there have been 512 team-games per season with a chance to put up 554 yards; in 1951, there were only 144. So how the heck did Van Brocklin throw for so many yards in one game and how has nobody broken that mark?

The Early ’50s Rams

Joe Stydahar’s Rams from ’50 to ’52 were the greatest show on grass a half century before the modern games. They ranked first in points in all three years, possessing a dominant offense in every way possible. Los Angeles led the league in passing yards in 1951, but this was no one-year wonder: the Rams threw for 427 in a game in 1950, and threw for over 300 yards in half their games that year. The ’52 team broke 300 yards only twice, topping out at 358 yards, but that team led the league in net yards per attempt for the third consecutive year. They were the dominant passing offense of their day, but they were far from one dimensional. Two running backs made the Pro Bowl each season, with Glenn Davis (aka Mr. Outside) and Dick Hoerner doing so in 1950, and then Dan Towler and Tank Younger earning those honors in each of the next three seasons. Towler, Younger and Hoerner were coined the Bull Elephant Backfield:

The idea for the bull elephants,” Dan recalled, “came during the 1950 season. We were playing a game in a sea of mud, and the coaches alternated backfields hoping to rest us. The coach then realized he had three fullbacks of equal running ability and saw what a powerful weapon he would have with two 200 pounders leading a third. “The next season, all of us were used together in rushing situations, as the year progressed, we were used as a unit more and more. We won the title that year, and I feel the `51 Rams was one of the greatest teams ever.

The passing game was even scarier, with Waterfield and Van Brocklin throwing to to two Hall of Famers (Elroy Hirsch and Tom Fears). A lineup of Van Brocklin at quarterback, Towler, Hoerner and Younger in the backfield, and Hirsch and Fears on the outside would cause nightmares for every defense they faced. But that was especially true on Friday, September 28, 1951.

554 — Naming your number

If you look at the boxscore from this game, a bunch of things jump out at you. The first, of course, is Van Brocklin’s stat line: 27 for 41, 554 yards and 5 touchdowns. And the Rams beat the New York Yanks, 54-14. But you’ll also see that it was a Friday game. Back then, Los Angeles used to begin the season with a Friday night game, as the Trojans owned the weekend back then. The next day, USC hosted San Diego Navy in that same Coliseum. The Rams and a few other teams (including the AAFC’s Dons, who also played in the Coliseum) occasionally played on Fridays, before Congress essentially stopped the practice in 1961.

The next thing you might notice is the opponent: the New York Yanks. I’ve written about Ted Collins’ 1951 Yanks before, which was akin to the modern Browns if the modern Browns moved cities every other year. That team went 1-9-2, finished last in points allowed and points differential, and were sold back to the NFL after the season (and purchased by Giles Miller’s group and moved to Dallas). This was barely a professional football team, and they scored both of their touchdowns against the Rams on defense and special teams. They passed for a dismal 8 yards against Los Angeles on that Friday night, despite dropping back 41 times. In the rematch later in the season — also in Los Angeles — the Rams mercifully took the air out of ball, rushing 44 times for 371 yards and 6 touchdowns.

If you pitted Tom Brady against a semi-pro team, he could surely throw for 560 yards if he wanted to. The question is, why would he want to? In the opener, the Rams were up 21-0 after the first quarter, and 34-0 in the first half. A punt return for a touchdown by the Yanks before half-time may have helped L.A. keep their foot on the gas; similarly, a 30-yard fumble return score in the 4th quarter might have been the motivation Stydahar and Van Brocklin needed to keep passing. Still, 42 passes in a 40-point win seems a bit high, no?

There have been only 15 games in league history where a team was up by at least 25 points at halftime and still threw over 40 times in the game, with over half coming since 2002. Three modern Patriots teams are on the list, but the first time it happened was in Van Brocklin’s record-setting performance against the Yanks. I wasn’t there, but we can safely assume that NVB padded the stats just a little bit. A New York Times report indirectly backs it up:

Van Brocklin almost made it six touchdown passes in the closing moments but Tommy Kalmanir was pulled down a yard short and Dan Towler punched it across. The Rams set a league record when they piled up 735 total yards, topping the old mark of 682 set by the Chicago Bears in 1943. Their 34 first downs beat by two their own record.

It’s unclear how many times the Rams threw up by 33 in the 4th quarter against a team that hadn’t scored a point on offense all day, but it’s hard to see why the answer would be more than zero. Without a play-by-play listing of the game, it’s tough to know exactly how many of Van Brocklin’s 554 yards came in “garbage time,” but it highlights a key reason why he still holds the record: teams don’t pad their stats the way they used to.

In the ’50s, if a team was throwing for 450 yards in a game, it was probably because the other team was really bad. Parity didn’t exist 50 years ago, and the spreads between the great teams and the bad ones was enormous. Van Brocklin throwing for 554 against the Yanks was a “name your number” sort of game, similar to when Alabama schedules an FSC school in November. Van Brocklin could have been pulled at half time (and perhaps would have if his co-star at quarterback, Bob Waterfield, was healthy) and it would have had no impact on the game. Now, quarterbacks set passing records when they play “good” teams, not “bad” teams. A high-scoring shootout could produce a 500-yard game; but if your opponent isn’t keeping pace, you’re not going to keep throwing passes all game (unless your team keeps turning the ball over near the goal line).

In Van Brocklin’s era, you put up huge numbers against terrible teams; now, quarterbacks put up huge numbers when they’re forced to throw from behind. So how does a modern passer throw for 555 yards? Clearly, they need to throw early and often. That can come from a great, accurate quarterback playing a team with a terrible pass defense and a high-scoring, high-octane offense; it could also happen if a team keeps driving down the field but turns the ball over or settles for field goals in the red zone. The classic shootout is always nice: Ben Roethlisberger threw for over 500 yards in a 37-36 win over the Packers when Aaron Rodgers was similarly efficient for Green Bay, and Super Bowl LII was an almost perfect setup for that type of record-breaking performance.

If you can get as many of the ideal factors below into one game, you’re in good shape (great quarterback play, assumed):

- Ineffective running game;

- Ineffective red zone play, by either settling for field goals, failing to convert on downs, or turning the ball over;

- A defense that gives up big plays and an opposing offense that can move down the field quickly (i.e., putting the offense back on the field quickly and with a need to score);

- An opposing defense that isn’t very good, and is also prone to big plays (lots of completions and long drives drain the clock); and

- Overtime.

Get all of those factors into a game, and NVB’s record just might fall. Brady was close in the Super Bowl, and some other star quarterback will come close again. But for now, nearly 67 years later, Norm Van Brocklin still stands alone.