by Chase Stuart

on June 7, 2014

Every year, I adjust quarterback statistics — both fantasy and traditional — for strength of schedule. Today, a look at my article at Footballguys.com where I adjust the 2013 numbers for each quarterback for the quality of the opposing defenses. On Monday, I’ll be doing the same for quarterbacks using Adjusted Net Yards per Attempt.

For the ninth straight season, I’m advising fantasy football owners about a good starting point for their quarterback projections/rankings. My Rearview QB article analyzes the production of every quarterback from the prior season after adjusting his performance for partial games played and strength of schedule. If you’re a first time reader, here’s my argument in a nutshell: using last year’s regular end-of-year data is the lazy man’s method. When analyzing a quarterback, many look at a passer’s total fantasy points or fantasy points per game average from the prior season and then tweak the numbers based on off-season changes and personal preferences. But a more accurate starting point for your projections is a normalized version of last year’s stats.

The first adjustment is to use adjusted games (and not total games), which provide a more precise picture of how often the quarterback played. Second, you should adjust for strength of schedule, because a quarterback who faced a really hard schedule should get a boost relative to those who played easy opponents most weeks.

To be clear, this should be merely the starting point for your quarterback projections. If you think a particular quarterback carries significant injury risk, or is going to face a hard schedule again, feel free to downgrade him after making these adjustments. (And it should go without saying that if you think a quarterback will improve or decline – or, in the case of Colin Kaepernick or Cam Newton his supporting case will improve or decline – you must factor that in as well.) But those are all subjective questions that everyone answers differently; this analysis is meant to be objective. The point isn’t to ignore whether a quarterback is injury prone or projects to have a really hard or easy schedule in 2014; the point is to delay that analysis.

First we see how the player performed on the field last year, controlling for strength of schedule and missed time; then you factor in whatever variables you like when projecting the 2014 season. The important thing to consider is that ignoring partial games and strength of schedule is a surefire way to misjudge a player’s actual ability level. There’s a big difference between a quarterback who produced 300 fantasy points against an easy schedule while playing every game than a quarterback with 300 FPs against the league’s toughest schedule while missing 3.6 games. Here’s another way to consider the same idea: Jay Cutler ranked 25th in fantasy points in 2013, but the quarterback position for the Bears (i.e., Cutler and Josh McCown) ranked as the 4th highest team QB last year.

You can read the full article here.

Tagged as:

Footballguys.com

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on May 31, 2014

Last year, I provided a starting point for my running back projections. The idea is pretty simple: some fantasy statistics are much more repeatable, or sticky, than others. Over at Footballguys.com, I used the following formula to help isolate those factors:

1) Rushing Yards (R^2 = 0.47). The best-fit formula to predict rushing yards is:

-731 + 3.73 * Rush Attempts + 180 * Yards/Rush

2) Receptions (R^2 = 0.42). The best-fit formula to predict receptions is:

11.1 + 0.39 * Receptions + 0.032 * Receiving Yards

3) Receiving Yards (R^2 = 0.38). The best-fit formula to predict receiving yards is:

83.7 + 1.65 * Receptions + 0.46 * Receiving Yards

4) Rushing Touchdowns (R^2 = 0.29). The best-fit formula to predict rushing touchdowns is:

0.1 + 0.0037 * Rushing Yards + 0.35 * Rushing Touchdowns

5) Receiving Touchdowns (R^2 = 0.23). The best-fit formula to predict receiving touchdowns is:

0.1 + 0.0022 * Receiving Yards + 0.25 * Receiving Touchdowns

Using these formulas, we can come up with a good starting point for your 2014 running back projections.

You can read the full article here.

Tagged as:

Footballguys.com

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on May 24, 2014

Green is poised for another monster year.

, at Footballguys.com, I looked at

the best starting point for wide receiver projections. Well, I’ve re-run the numbers and come up with

the best starting point for wide receiver projections in 2014.

The general philosophy is that receiving yards can be re-written using the following formula:

Receiving yards = (Receiving Yards/Target) x (Targets/Team_Pass_Att) x Team_Pass_Att.

Since each of those variables regress to the mean in different ways, we can get a more accurate projection of future receiving yards by projecting each of those three variables than by simply looking at past receiving yards. For example, here are the best fit formulas for each of those metrics:

Future Pass Attempts = 36 + (450 x Pass_Attempts/Play) + (0.255 x Offensive Plays)

Future Percentage of Targets = 6.2% + 71.3% x Past Percentage of Targets

Future Yards/Target = 5.5 + 0.29 x Past Yards/Targets

If you take a look at the three coefficients, the number of offensive plays run from year to year and the yards per target averages are not very sticky; both have coefficients of less than 0.3, which indicates a significant amount of regression to the mean. Meanwhile, percentage of targets is much, much sticker, at 71%.

As a result, this regression really likes players like A.J. Green (5th in receiving yards in 2013, projected to be 1st in 2014), Andre Johnson (7th, 2nd) and Vincent Jackson (14th, 6th). To find out who else this metric likes and dislikes, and for a more thorough analysis, you can read the full article here.

Tagged as:

Footballguys.com

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on March 20, 2014

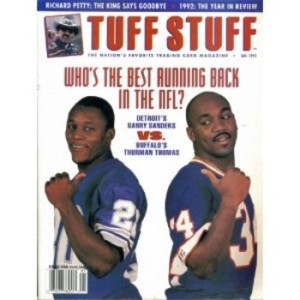

Don't worry, this picture's presence will make sense by the end. I think.

Two years ago, I wrote

this post on running back aging curves. One conclusion from my research was that age 26 was the peak age for running backs, which was immediately followed by a steady decline phase until retirement. In that study, I only wanted to look at very good-to-excellent running backs in the modern era; as a result, I was forced to limit myself to just 36 players. I’ve been meaning to update that post, but wasn’t quite sure what methodology to use.

Last year, Neil wrote a very interesting post on quarterback aging curves. In it, Neil computed the year-to-year differences in Relative ANY/A at every age. While reviewing that post, a lightbulb went off. We can greatly increase the sample size if we only look at running backs from year-to-year, and not just the best running backs on the career level.

There are 723 running backs since 1970 who had at least 150 carries in consecutive seasons and who were between 21 and 32 in the first of those two seasons. For each running back pair of seasons, I calculated how many rushing yards the player gained in Year N and many yards he gained in Year N+1. Take a look:

[continue reading…]

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on December 8, 2013

Just above these words, it says “posted by Chase.” And it was literally posted by Chase, but the words below the line belong to Steve Buzzard, who has agreed to write this guest post for us. And I thank him for it. Steve is a lifelong Colts fan and long time fantasy football aficionado. He spends most of his free time applying advanced statistical techniques to football to better understand the game he loves and improve his prediction models.

The way to win fantasy football games is to have players that score a lot of points. Players tend to score more points when they get more touches. One of the most important factors in determining how many touches each player is going to have is to determine the Game Script ahead of time. As we all know positive game scripts result in more passing attempts and negative Game Scripts result in more rushing attempts. But I am going to try to project the pass ratio using two key stats, Pass Identity rating and the Vegas spreads. We can use these projected pass ratios to build our own projections or at least look for outliers and figure out how to adjust players from their year to date averages.

Regular readers know what Pass Identity means. For newer readers, you can read here to see how Pass Identities are calculated. But the quick summary is that Pass Identity grades allow us to predict the pass ratio of any game where the point spread is zero. This is because Pass Identity tries to eliminate the Game Script from the pass ratios. For example since the Bears/Cowboys game is a pick’em this week, we can predict the pass ratio of the Bears by using the following formula. League average pass ratio + (A + B) *C, where

(A) = number of standard deviations above/below average the Bears are in Game Script (-0.49);

(B) = number of standard deviations above/below average the Bears are in Pass Ratio (+0.53); and

(C) = the standard deviation among the thirty-two teams with respect to Pass Ratio (5.3%)

Of course, the product of (A) and (B) is the Pass Identity grade for each team; once we determine that, we multiply that number by the standard deviation of the pass ratios of all teams to get us a prediction for the pass ratio in a game with a Game Script of 0.0. Since the Bears have a Pass Identity of basically 100, the projected Pass Ratio for Chicago against Dallas is 58.9%.

We can then compare this projection to Chicago’s year-to-date pass ratio of 61.5% and predict that all else equal Jay Cutler and the passing game should score about 4% less this week than their average week where as Matt Forte and the run game would score about 4% more.

[continue reading…]

Tagged as:

Game Scripts,

Guest Posts

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on October 26, 2013

Richardson powers through for three yards.

has been a frequent topic of discussion at Football Perspective. In about 14 months, I’ve written the following articles:

- How often does the first running back selected in the draft become the best running back from his class? The field is always a better bet than one player: Only about 40% of the highest-drafted backs led their class in rushing yards as a rookie, with that number dropping to about 33% on a career basis. On the other hand, that’s better than the production of the first-drafted wide receiver.

- In 2012, the field won, as both Doug Martin and Alfred Morris rushed for more yards than Richardson. I then tried to project the number of yards for all three players for 2013 based on their draft status and rookie production; as it turns out, draft status remained extremely important, and Richardson projected to average the most yards per game in year two out of that group (a projection that doesn’t look very good right now).

- In July, I continued to voice my disdain for the use of yards per carry as the main statistic for running backs, when I argued that Richardson’s 3.6 average last year was not important. More specifically, I said if you loved Richardson as a prospect, his 3.6 YPC average in 2012 was not a reason to downgrade him (of course, if you didn’t like Richardson, that’s a different story). Richardson still received a huge percentage of Cleveland carries and had a strong success rate, and I argued that his low YPC was simply a function of a lack of big plays. For a more in-depth breakdown of his rookie season, Brendan Leister compiled a good film-room breakdown of some of Richardson’s mistakes in 2012. Leister noted that Richardson had some mental mistakes, which isn’t atypical of a rookie, and still fawned over the former Alabama star’s physical potential.

- After the trade to Indianapolis, I wrote that Richardson’s ability as a pass blocker was tough to analyze, and advised you to view some of the numbers thrown around in support of Richardson with skepticism. Believe it or not, I still have thoughts on that trade that I just haven’t gotten around to finishing, so look for my hot take on the Richardson deal to be published in say, March.

In 75 carries with the Colts, Richardson is averaging just 3.0 yards per carry. Even though I find yards per carry overrated, there is a certain baseline level of production needed for every running back, and 3.0 falls well short of that number. For his career, Richardson now has 1,283 yards on 373 yards, a 3.44 YPC average. He’ll reach 400 career carries in a couple of weeks, so I thought it might be interesting to look at the YPC averages of all running backs after their first 400 carries.

We can’t measure that exactly through game logs, but what we can do is calculate the career YPC average of each running back after the game in which they hit 400 career carries. The table below shows that number for all running backs who entered the league in 1960 or later and is current through 2012. Let’s start with the top 50 running backs:

[continue reading…]

Tagged as:

Trent Richardson,

Yards per rush

{ }

by Neil Paine

on August 25, 2013

This guy's 1982 Chargers sure come up a lot when we do lists like these.

More than a decade ago (on a side note: how is

that possible?), Doug

wrote a series of player comments highlighting specific topics as they related to the upcoming fantasy football season. I recommend that you

read all of them, if for no other reason than the fact you should make it a policy to read everything Doug Drinen ever wrote about football, but today we’re going to focus on

the Isaac Bruce comment, which asked/answered the question:

Is this Ram team the biggest fantasy juggernaut of all time?

“This Ram team,” of course, being the 1999, 2000, & 2001 Greatest Show on Turf St. Louis Rams. At the time, Doug determined that those Rams were not, in fact, the best real-life fantasy team ever assembled, by adding up the collective VBD for the entire roster. They ranked tenth since 1970; the top 10 were:

1. 1. 1975 Buffalo Bills – 550 Simpson (281) Ferguson (98) Braxton (83) Chandler (44) Hill (42)

2. 1982 San Diego Chargers – 542 Chandler (190) Fouts (126) Winslow (121) Muncie (92) Brooks (10) Joiner (1)

3. 1994 San Francisco 49ers – 514 Young (208) Rice (140) Watters (98) Jones (67)

4. 1995 Detroit Lions – 478 Mitchell (136) Moore (132) Sanders (121) Perriman (87)

5. 1984 Miami Dolphins – 470 Marino (243) Clayton (145) Duper (76) Nathan (6)

6. 1998 San Francisco 49ers – 467 Young (200) Hearst (137) Owens (81) Rice (46) Stokes (1)

7. 1986 Miami Dolphins – 456 Marino (210) Duper (94) Clayton (76) Hampton (61) Hardy (13)

8. 2000 Minnesota Vikings – 452 Culpepper (170) Moss (123) Smith (87) Carter (70)

9. 1991 Buffalo Bills – 449 Thomas (157) Kelly (143) Reed (80) Lofton (51) McKeller (17)

10. 1999 St. Louis Rams – 435 Faulk (184) Warner (179) Bruce (71)

As an extension of Chase’s recent post on the The Best Skill Position Groups Ever, we thought it might be useful to update Doug’s study in a weekend data-dump post. I modified the methodology a bit — instead of adding up VBD for the entire roster, for each team-season I isolated the team’s leading QB and top 5 non-QBs by fantasy points (using the same point system I employed when ranking the Biggest Fluke Fantasy Seasons Ever). I then added up the total VBD of just those players, to better treat each roster like it was a “real” fantasy team.

Anyway, here are the results. Remember as well that VBD is scaled up to a 16-game season, so as not to short-change dominant fantasy groups from strike-shortened seasons (:cough:1982 Chargers:cough:).

[continue reading…]

{ }

by Neil Paine

on August 10, 2013

Yesterday, I set up a method for ranking the flukiest fantasy football seasons since the NFL-AFL merger, finding players who had elite fantasy seasons that were completely out of step with the rest of their careers. I highlighted fluke years #21-30, so here’s a recap of the rankings thus far:

30. Lorenzo White, 1992

29. Dwight Clark, 1982

28. Willie Parker, 2006

27. Lynn Dickey, 1983

26. Robert Brooks, 1995

25. Ricky Williams, 2002

24. Jamal Lewis, 2003

23. Mark Brunell, 1996

22. Vinny Testaverde, 1996

21. Garrison Hearst, 1998

Now, let’s get to…

The Top Twenty

20. RB Natrone Means, 1994

| Best Season |

| year | g | rush | rushyd | rushtd | rec | recyd | rectd | VBD |

| 1994 | 16 | 343 | 1,350 | 12 | 39 | 235 | 0 | 103.0 |

| 2nd-Best Season |

| year | g | rush | rushyd | rushtd | rec | recyd | rectd | VBD |

| 1997 | 14 | 244 | 823 | 9 | 15 | 104 | 0 | 12.9 |

Big, bruising

Natrone Means burst onto the scene in 1994 as a newly-minted starter for the Chargers’ eventual Super Bowl team, gaining 1,350 yards on the ground with 12 TDs. In the pantheon of massive backs, he was supposed to be the AFC’s answer to the Rams’

Jerome Bettis, but Means was slowed by a groin injury the following year and never really stayed healthy enough to recapture his old form. The best he could do was to post a pair of 800-yard rushing campaigns for the Jaguars & Chargers in 1997 & ’98 before retiring after the ’99 season.

19. WR Braylon Edwards, 2007

| Best Season |

| year | g | rec | recyd | rectd | VBD |

| 2007 | 16 | 80 | 1,289 | 16 | 107.7 |

| 2nd-Best Season |

| year | g | rec | recyd | rectd | VBD |

| 2010 | 16 | 53 | 904 | 7 | 15.4 |

The 3rd overall pick in the

2005 Draft out of Michigan, Edwards seemingly had a breakout 2007 season catching passes from fellow Pro Bowler

Derek Anderson. But both dropped off significantly the next season, and Edwards was sent packing to the Jets in 2009. He did post 904 yards as a legit starting fantasy wideout in 2010, but he has just 380 receiving yards over the past 2 seasons, and it’s not clear he’ll ever live up to those eye-popping 2007 numbers again.

[continue reading…]

{ }

by Neil Paine

on August 9, 2013

I prefer cooking in a Garrison Hearst replica jersey.

There’s nothing like a truly great fluke fantasy season. Because they can help carry you to a league championship (and therefore eternal bragging rights —

flags fly forever, after all), a random player who unexpectedly has a great season will often have a special place in the heart of every winning owner. And even if you

only use their jerseys as makeshift aprons to cook in, fluke fantasy greats are a part of the fabric of football fandom. That’s why this post is a tribute to the greatest, most bizarre, fluke fantasy seasons of all time (or at least since the 1970 NFL-AFL merger).

First, a bit about the methodology. I’m going to use a very basic fantasy scoring system for the purposes of this post:

- 1 point for every 20 passing yards

- 1 point for every 10 rushing or receiving yards

- 6 points for every rushing or receiving TD

- 4 points for every passing TD

- -2 points for every passing INT

I’m also measuring players based on Value Based Drafting (VBD) points rather than raw points. In a nutshell, VBD measures true fantasy value by comparing a player to replacement level, defined here as the number of fantasy points scored by the least valuable starter in your league. For the purposes of this exercise, I’m basing VBD on a 12-team league with a starting lineup of one QB, two RBs, 2.5 WRs, and 1 TE. That means we’re comparing a player at a given position to the #12-ranked QB, the #24 RB, the #30 WR, or the #12 TE in each season. If a player’s VBD is below the replacement threshold at his position, he simply gets a VBD of zero for the year.

[continue reading…]

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on August 1, 2013

If you don’t play fantasy football, you probably have no idea what this title means. Of course, it’s 2013, so if you don’t play fantasy football, you’re now the oddball. “PPR” stands for points per reception. About half of all fantasy leagues do not give any points for receptions, while the other half includes some sort of PPR format. And while the value of every player is dependent on each league’s scoring system, few players see their value fluctuate between scoring systems quite like Wes Welker. Or, at least, that’s how it seems. Is there a way to measure this effect?

First, a review of Welker’s numbers since he joined the Patriots:

Welker doesn’t get many touchdowns, and while he has respectable yardage totals, he is only exceptional when it comes to piling up receptions. Welker has 672 receptions over the last six seasons, easily the most in the NFL (in fact, it’s the most ever over any six-year stretch). Brandon Marshall (592) and Reggie Wayne (578) are the only two players even within 100 catches of Welker. Over that same time frame, he ranks 4th in receiving yards, but only tied for 17th in receiving touchdowns.

Giselle approves of Welker's form.

So how can we measure how much more valuable Welker is in PPR-leagues than non-PPR leagues? One way is to use

VBD, which is a measure of how much value a player provided over the worst starter (or some other baseline). For example, Welker scored 173 fantasy points and ranked as WR12 in non-PPR leagues last season. If you are in a start-three wide receiver league, the worst starter would be WR36, who scored 111 fantasy points. That means Welker provided 62 points of VBD.

[continue reading…]

Tagged as:

Broncos,

Footballguys.com,

RPO 2013,

VBD,

Wes Welker

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on July 21, 2013

For eleven straight years, I’ve written an article called “Defensive Team By Committee.” This year’s version is up at Footballguys.com (subscriber only).

Fantasy defenses are inconsistent from year to year, making it difficult to predict which defenses and special teams (D/STs) will excel. And, at least in theory, the teams available at the ends of your drafts should provide less rewards. So how do you get great production out of the position while saving your most important draft picks?

We spend countless hours analyzing team offenses, and relatively few thinking about team defenses. But an average defense against a bad offense will do just as well as a great defense against an average offense. The key to the DTBC system is to find two teams available late in your draft whose combined schedule features predominantly weak offenses. By starting your defense based on matchups, your D/ST will generally face a weak offense, meaning your D/ST position will score lots of fantasy points.

You can read my two picks, along with a ranking of all 496 combinations, here.

For you iPad users our there, I’ll also recommend the $4.99 Footballguys Fantasy Football Magazine Draft Kit, an awesome resource at a super cheap cost. That includes the Draft GM Kit, which you can separately order if (like me) you don’t have an iPad but do have an iPhone. Both products will also be available on Android very soon, if not already by the time you read this. You can receive all Footballguys updates by signing up on the Free Footballguys Daily E-mail list.

Tagged as:

Footballguys.com

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on July 14, 2013

[Note: For the rest of the year, content over at Footballguys.com is subscriber-only.]

Over at Footballguys.com, I build upon Joe Bryant’s VBD and create the idea of Expected VBD. While VBD is a great way to understand the value of players, Expected VBD explains how we draft. This concept is why even though you may expect some kickers and fantasy defenses to perform well, you don’t take them early in the draft because they have low Expected VBDs. So what is Expected VBD?

Instead of drafting according to strict VBD, you should be drafting to something I’ll call Expected VBD, which is best defined by an example. Suppose Russell Wilson has three equally possible outcomes this year: he has a one-in-three chance of scoring 425 fantasy points, 325 fantasy points, and 225 fantasy points. Further, let’s assume that the baseline number of fantasy points at the quarterback position is 300 fantasy points.

We would project Wilson to score 325 points, which would be the weighted average of his possible outcomes. This means VBD would tell you that he is worth 25 points, because 325 is 25 points above the baseline. Expected VBD works like this: If Wilson scores 425 points, he’ll produce 125 points of VBD. If he scores only 325 points, he’ll be worth +25, and if he scores only 225 points, he’s going to have -125 points of VBD. In real life, players with negative VBD scores can be released or put on your bench. So if Wilson scores 225 points (probably due to injury), you’ll start another quarterback, roughly a quarterback who can give you baseline production.

So when Wilson scores 225 fantasy points, his VBD is 0, not -75. That means his Expected VBD would be (125+25+0)/3, or 50. Wilson’s VBD according to our projections may be only 25, but his Expected VBD is twice as large because Expected VBD does not provide an extra penalty for sub-baseline performances. Not surprisingly, different positions have different amounts of Expected VBD associated with them.

Below is the summary graph — it has quickly become one of my all-time favorite graphs — which shows the Expected VBD by each position according to Average Draft Position.

I go into much more detail in the full article.

Tagged as:

Footballguys.com

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on June 20, 2013

In 2008, Larry Fitzgerald had a fantastic regular season capped off by a historically great postseason; in the Super Bowl, he set the record for receiving yards in a season, including playoff games, with 1,977 yards. Of course, 2008 was decades ago in today’s era of what have you done for me lately. The table below shows Fitzgerald’s stats over the past four seasons. The final two columns show the total number of receiving yards generated by all Cardinals players and Fitzgerald’s share of that number.

| Year | Rec | Yds | YPR | TD | ARI Rec Yds | Perc |

| 2009 | 97 | 1092 | 11.3 | 13 | 4200 | 26% |

| 2010 | 90 | 1137 | 12.6 | 6 | 3264 | 34.8% |

| 2011 | 80 | 1411 | 17.6 | 8 | 3954 | 35.7% |

| 2012 | 71 | 798 | 11.2 | 4 | 3383 | 23.6% |

2009 was the last season of the Kurt Warner/Anquan Boldin Cardinals. The 97 receptions and 13 touchdowns look great, although hitting those marks and not gaining 1,100 receiving yards is very unusual. Fitzgerald was only responsible for 26% of the Cardinals receiving yards that season, although one could give him a pass since he was competing with another star receiver for targets.

Can Fitzgerald rebound in 2013?

In 2010,

Derek Anderson,

John Skelton,

Max Hall, and

Richard Bartel were the Cardinals quarterbacks: as a group, they averaged 5.8 yards per attempt on 561 passes. Arizona’s passing attack was bad, but without Boldin, Fitzgerald gained 34.8% of the team’s receiving yards.

Steve Breaston chipped in with 718 receiving yards yards while a 22-year-old

Andre Roberts was third with 307 yards. In other words, Fitzgerald performed pretty much how you would expect a superstar receiver to perform on a team with a bad quarterback and a mediocre supporting cast: his raw numbers were still very good (but not great) because he ate such a huge chunk of the pie. After the 2010 season, I even

wondered if he could break any of

Jerry Rice’s records (spoiler: he can’t).

In 2011, Skelton, Kevin Kolb and Bartel combined for 3,954 yards on 550 passes, a 7.2 yards per attempt average (Kolb was at 7.7 Y/A). That qualifies as a pretty respectable passing game and Fitzgerald appeared to have a monster year, gaining 35.7% of the Cardinals’ receiving yards (Early Doucet was second with 689 yards and Roberts was third with 586 yards). It’s always hard splicing out cause and effect, but my takeaway is that with a more competent passing game, Fitzgerald continued to get the lion’s share of the team’s production but unlike in 2010, this led to great and not just good numbers.

[continue reading…]

Tagged as:

aDOT,

Air Yards,

Cardinals,

Larry Fitzgerald,

RPO 2013

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on June 16, 2013

Over at Footballguys.com, I look at a different method to project receiving yards.

The number of receiving yards a player produces is the result of a large number of variables. Some of them, like the receiver’s ability, are pretty consistent from year to year. But other factors are less reliable, or less “sticky” from year to year. I thought it would be informative to look at three key variables that impact the number of yards a wide receiver gains and measure how “sticky” they are from year to year. These three variables are:

- The number of pass attempts by his team;

- The percentage of his team’s passes that go to him; and

- The receiver’s average gain on passes that go to him.

We can redefine receiving yards to equal the following equation:

Receiving yards = Receiving Yards/Target x Targets/Team_Pass_Att x Team_Pass_Att.

You’ll notice that Targets and Team Pass Attempts are in both the numerator and denominator of one of the fractions, and they will cancel each other out: that’s why this formula is equivalent to receiving yards.

By breaking out receiving yards into these three variables, we can then examine the stickiness of each one, which should help our Year N+1 projections. Below are the best-fit equations for each of those variables in Year N+1:

Future Pass Attempts = 36 + (450 x Pass_Attempts/Play) + (0.255 x Offensive Plays)

Future Percentage of Targets = 6.2% + 71.3% x Past Percentage of Targets

Future Yards/Target = 5.5 + 0.29 x Past Yards/Targets

I then used those three equations to come up with a starting point for receiving yards projections for 28 wide receivers. You can read the full article here.

Tagged as:

Footballguys.com

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on June 2, 2013

Over at Footballguys.com, I explain my method of how to value a player that we know is going to a certain number of games. You can’t simply use the player’s projected number of fantasy points because that will underrate him. But if you go by his projected points per game average, he’ll be overrated. Using Rob Gronkowski as an example, I explained my method:

First, you need to determine the fantasy value of a perfectly healthy Gronkowski. Prior to today’s news, David Dodds had projected Gronkowski to record 70 catches for 938 yards and 9 touchdowns… but in only 14 games. This means Dodds had projected the Patriots star to average 10.6 FP/G in standard leagues, 15.6 FP/G in leagues that award one point per reception, and 18.1 FP/G in leagues like the FFPC that give tight ends 1.5 points per reception.

But those numbers aren’t useful in a vacuum: the proper way to value a player isn’t to look at the number of fantasy points he scores. Instead, the concept of VBD tells us that a player’s fantasy value is a function of how many fantasy points he scores relative to the other players at his position. I like to use a VBD baseline equal to that of a replacement player at the position, and “average backup” is a good proxy for that. In a 12-team league that starts one tight end with no flex option, that would be TE18. In standard leagues, TE18 on a points per game basis is Brandon Myers, the ex-Raiders tight end now with the Giants. Footballguys projects Myers to average 5.4 FP/G in standard leagues and and 8.9 FP/G in PPR leagues. In 1.5 PPR leagues, Martellus Bennett comes in at TE18 in our projections, with an average of 10.6 FP/G.

You can read the full article, which includes a neat table, here.

Tagged as:

Footballguys.com,

Rob Gronkowski

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on June 2, 2013

At Footballguys.com, I explain why fantasy football owners need to understand the concept of regression to the mean. Readers of this blog probably don’t need the long background, but you might enjoy some of the graphs at the end. For example, this is the distribution of yards per carry in Year N and yards per carry in Year N+1:

You can read the full article here.

Tagged as:

Footballguys.com

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on May 26, 2013

Over at Footballguys.com, I identified which quarterback statistics are repeatable and which ones are most likely to regress to the mean. I also ran a regression using touchdown length as my input and future touchdowns as my output.

From 1990 to 2011, 188 different quarterbacks started at least 14 games and thrown 300+ passes in one year, and then attempted at least 300 passes for the same team the next season. After analyzing the lengths of each touchdown pass for those quarterbacks, I discovered the following:

- For every one-yard touchdown pass in Year N, expect 0.70 touchdowns in Year N+1

- For every two-to-five-yard touchdown pass in Year N, expect 0.56 touchdowns in Year N+2

- For every six-to-ten-yard touchdown pass in Year N, expect 0.77 touchdowns in Year N+2

- For every 11-to-20-yard touchdown pass in Year N, expect 0.70 touchdowns in Year N+2

- For every 21-to-30-yard touchdown pass in Year N, expect 0.22 touchdowns in Year N+2

- For every 31-to-50-yard touchdown pass in Year N, expect 0.33 touchdowns in Year N+2

- For every 50+ yard touchdown pass in Year N, expect 0.33 touchdowns in Year N+2

If a team throws touchdowns from inside the red zone, that reveals an offensive philosophy that is good for your fantasy quarterback. On the other hand, 21+ yard touchdowns might make the highlight feels, but are very unpredictable from year to year. What does that mean for 2013?

You can view the full article here.

Tagged as:

Footballguys.com

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on May 19, 2013

Over at Footballguys.com, I analyzed how the fantasy value of quarterbacks, running backs, wide receivers, and tight ends have changed since 1990. The NFL is a very different beast than it was 23 years ago, but you might be surprised to see what that means for fantasy football. To measure value, I examined the VBD curves for each of the four major positions in fantasy football.

For those unfamiliar with VBD, you can read Joe Bryant’s landmark article here. The guiding principle is that the value of a player is determined not by the number of points he scores but by how much he outscores his peers at his particular position. This means that in a league that starts 12 quarterbacks, each quarterback’s VBD score is the difference between his fantasy points and the fantasy points scored by the 12th best quarterback. The cut-offs at the other positions are 12, 24, and 36, for tight ends, running backs, and wide receivers, respectively.

The NFL in 2013 won’t closely resemble how the league looked in 1990, but what does that mean for fantasy football? To determine that, we need to see if VBD has evolved with the rest of the football statistics. Let’s start with a graph displaying number of fantasy points scored by the last starter at each position since 1990. As you can see, quarterback scoring has risen significantly over the last two decades, and the production of the 12th tight end has nearly doubled over that time period.

You can see the full article here.

Tagged as:

Footballguys.com

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on May 17, 2013

Green Bay didn’t use a first round pick on a running back, but the Packers did spend a second round pick on Alabama’s Eddie Lacy and a fourth round pick on UCLA’s Johnathan Franklin. How much weight should we put on draft status when one team drafts two running backs just a couple of rounds apart? One school of thought is that the Packers liked both players and are maximizing their odds of finding a star; another is that Green Bay prefers Lacy and wants him to win the job, since he was their first choice. Here’s another thing to consider, courtesy of my good buddy Sigmund Bloom: the Packers traded down to grab Lacy and traded up to draft Franklin, indicating that perhaps the Packers were higher on Franklin than you might think.

How rare is it for teams to double dip at the running back position like this? That depends on how you want to categorize what the Packers did. I think a reasonable comparison would be to look at all teams that:

- Did not draft a running back in the first round but drafted one in the second or third rounds (this excludes combinations like Stepfan Taylor and Andre Ellington); and

- Then drafted a different running back within the next two rounds

Since 1970, only 34 teams have met those criteria, meaning this is a strategy employed roughly three times every four years. In three instances, a team drafted three running backs that met those two criteria, and we’ll deal with them at the end of this post. I’m going to exclude three teams that drafted fullbacks after selecting halfbacks, as the 2008 Lions (drafted Jerome Felton after Kevin Smith), 2003 Ravens (Ovie Mughelli after Musa Smith), and 1999 Dolphins (Rob Konrad after J.J. Johnson) don’t really fit the intent of the post. That leaves us with 28 pairs of running backs. The table below lists each pair. On the left, you will see the first running back drafted, his round and overall pick, his rookie rushing yards, his rookie fantasy points total (using 0.5 points per reception), and his career rushing yards; on the right, the same information is presented for the second running back drafted. The far right column shows the difference between the two players in terms of fantasy points during their rookie year. For example, Stevan Ridley scored 41 more points than Shane Vereen in 2011, even though the Patriots drafted Vereen first.

[continue reading…]

Tagged as:

Eddie Lacy,

Johnathan Franklin

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on May 5, 2013

As most of you know, I also write for Footballguys.com, what I consider to be the best place around for fantasy football information. If you’re interested in fantasy football or like reading about regression analysis, you can check out my article over at Footballguys on how to derive a better starting point for running back projections:

Most people will use last year’s statistics (or a three-year weighted average) as the starting point for their 2013 projections. From there, fantasy players modify those numbers up or down based on factors such as talent, key off-season changes, player development, risk of injury, etc. But in this article, I’m advocating that you use something besides last year’s numbers as your starting point.

There is a way to improve on last year’s numbers without introducing any subjective reasoning. When you base a player’s fantasy projections off of his fantasy stats from last year, you are implying that all fantasy points are created equally. But that’s not true: a player with 1100 yards and 5 touchdowns is different than a runner with 800 yards and 10 touchdowns.

Fantasy points come from rushing yards, rushing touchdowns, receptions, receiving yards, and receiving touchdowns. Since some of those variables are more consistent year to year than others, your starting fantasy projections should reflect that fact.

The Fine Print: How to Calculate Future Projections

There is a method that allows you to take certain metrics (such as rush attempts and yards per carry) to predict a separate variable (like future rushing yards). It’s called multivariate linear regression. If you’re a regression pro, great. If not, don’t sweat it — I won’t bore you with any details. Here’s the short version: I looked at the 600 running backs to finish in the top 40 in each season from 1997 to 2011. I then eliminated all players who did not play for the same team in the following season. I chose to use per-game statistics (pro-rated to 16 games) instead of year-end results to avoid having injuries complicated the data set (but I have removed from the sample every player who played in fewer than 10 games).

So what did the regression tell us about the five statistics that yield fantasy points? A regression informs you about both the “stickiness” of the projection — i.e., how easy it is to predict the future variable using the statistics we fed into the formula — and the best formula to make those projections. Loosely speaking, the R^2 number below tells us how easy that metric is to predict, and a higher number means that statistic is easier to predict. Without further ado, in ascending order of randomness, from least to most random, here is how to predict 2013 performance for each running back based on his 2012 statistics:

You can read the full article here.

Tagged as:

Footballguys.com

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on February 15, 2013

On Monday, I argued that target data has some predictive value. I wanted to update that post with a few observations.

Wide Receiver Targets

In the original post, I looked at year-to-year data for all players with at least 500 receiving yards in Year N and at least 8 games played for the same team in Years N and N+1. But it makes more sense to limit the sample to only wide receivers if we want to predict how wide receivers project in the next season.

There are 554 pairs of wide receiver seasons that meet the above criteria. The best fit formula to project future receptions based on prior receptions and prior targets is:

Year N+1 Receptions = 14.0 + 0.547 * Yr_N_Rec + 0.124 * Yr_N_Tar

The R^2 is 0.39, and while the receptions variable is statistically significant by any measure, the targets variable just barely qualifies (p = 0.044) as such. Still, this tells us that for every 8 additional targets a receiver sees in Year N, we can expect one more reception in Year N+1, holding his number of receptions equal.

If we want to project receiving yards instead of receptions, we get:

Year N+1 Receiving Yards = 180.3 + 0.434 * Yr_N_RecYd + 2.55 * Yr_N_Tar

The R^2 is 0.33, implying a slightly less strong relationships, which makes sense: yards are more variable to large outliers than receptions, so you would expect receiving yards to be slightly harder to predict. Another interesting note: the targets variable here is statistically significant at the p = 0.0003 level, and as expected, the receiving yards variable is statistically significant at all levels. Holding receiving yards equal, a receiver would need an additional 19 targets to increase his projected number of receiving yards by 50, so the practical effect may not be all that large.

Addressing the multicollinearity problem

[continue reading…]

Tagged as:

Calvin Johnson,

Targets,

WR Project

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on December 11, 2012

Because I am an enormous narcissist, I wondered if I could find the very first article I ever wrote. And I did. While I doubt anyone visiting the site today wants to read an article by a first-time writer from the summer of 2002, if you do, here is my article discussing the fantasy relevance of a defense when ranking running backs. Here is the intro:

Being the most important position in fantasy football, running backs are analyzed and examined from just about every angle. Most fantasy footballers can tell you who slumped in the 2nd half, who had a great ypc, and who had a ton of “fluky” TDs last year that won’t likely happen again. One factor a lot of owners look into is the defense of a RB. Logic dictates that the RBs on good defenses are like gold mines: see Eddie George the past few years, Jamal Lewis and A-Train when their teams Ds had breakout seasons, and the original superstar of modern fantasy football, Emmitt Smith. 4 straight years as the number 1 RB, and his team’s D was in the top 5 all 4 years. Teams with great Ds are notorious for pounding the ball late in game, running a lot early in games(so as to not throw interceptions, and win the battle of field position and win it with your defense), and basically pad your RBs stats. While some put more weight than others on the importance of a strong D(some view it as very important, others as a deciding factor between 2 backs they rate similarly), it appears the correct weight to put on a defense when evaluating a RB is 0. Zilch. Nothing. Meaningless. Let’s take a look at last year:

| RB | Yards | DPA | DPYA | DRYA | TDs | Year | DTR |

| Holmes | 1555 | 23 | 13 | 27 | 8 | 2001 | 21 |

| Martin | 1513 | 12 | 5 | 28 | 10 | 2001 | 15 |

| S. Davis | 1432 | 13 | 3 | 20 | 5 | 2001 | 12 |

| Green | 1387 | 5 | 15 | 16 | 9 | 2001 | 12 |

| Faulk | 1382 | 7 | 10 | 3 | 12 | 2001 | 7 |

| Alexander | 1318 | 18 | 23 | 15 | 14 | 2001 | 19 |

| Dillon | 1315 | 14 | 14 | 11 | 10 | 2001 | 13 |

| Williams | 1245 | 27 | 20 | 14 | 6 | 2001 | 20 |

| Tomlinson | 1236 | 16 | 19 | 19 | 10 | 2001 | 18 |

| Hearst | 1206 | 9 | 18 | 9 | 4 | 2001 | 12 |

| Avg | 1359 | 14 | 14 | 16 | 9 | | 15 |

Yards is the rushing yards, DPA is the POINTS ALLOWED RANK by that RBs defense, DPYA and DRYA are the rank that RBs team fared in Passing and Rushing yards allowed respectively, and TDs are rushing TDs for that RB. DTR is the average of the 3 defensive categories. The top 2 RBs last year were on teams with defenses who were in the bottom 5 of the league against the run. Using “common theory’, one would figure that teams that can’t stop the run, can’t control the clock, get behind early, and have to pass more. Those who backed off on Holmes and Martin due to their poor Ds(and Stephen Davis included) missed out. On average, the top 10 rushers in the league had well, average defenses. Middle of the pack in terms of points allowed, rushing yards allowed and passing yards allowed. Is this a one year trend?

I think it was Doug Drinen who once said if you don’t look at something you wrote five years ago and cringe, then you aren’t improving as a writer. For ten years old, this article seems to hold up okay although it could certainly use some editing. Fortunately, the conclusion is cringe-inducing enough for me to be convinced that I have improved from my first piece to my last.

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on December 11, 2012

Richard Sherman exhibits the proper form for 'You Mad Bro?' in sign language.

Bill Barnwell wrote yesterday about the

dominant fantasy performance by the Seahawks defense against Arizona on Sunday. The Seahawks scored two touchdowns, forced 8 turnovers, recorded three sacks, and pitched a shutout. That made me wonder: which defense produced the best fantasy in NFL history?

I used Footballguys.com’s scoring system in the Footballguys Players Championship to calculate every performance by a fantasy D/ST since 1940. Here it is:

Because I decided to use the official scoring designation for every play and chose not to rewatch every game in NFL history, there is one error that will come up in every few hundred games. Occasionally, an offense will score a touchdown on its own fumble recovery and that goes down in the gamebooks as a fumble recovery just like a defensive touchdown. So, be warned, these are unofficial fantasy scores.

As it turns out, Seattle’s game against Arizona comes in tied for 10th place. Incredibly, the best performance by a fantasy defense — a whopping 52 points — came in a Steelers-Browns game but wasn’t delivered by Pittsburgh. The came in the 1989 season opener, and after losing 41-10 the following week, Pittsburgh rebounded to finish 9-7 and make the playoffs. In 1950, the New York Giants also scored 52 fantasy points against the Steelers. New York scored 18 points in that game — 2 safeties, two fumble return touchdowns — and forced 9 turnovers and 7 sacks. The table below lists the best performances by a fantasy defense:

[continue reading…]

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on August 24, 2012

Tomlinson pushed many teams to fantasy titles.

Bill Simmons wrote about LaDainian Tomlinson last month and called him the best fantasy football player of all-time. “Greatest ever” debates are always subjective, but at least when it comes to fantasy football, we can get pretty close to declaring a definitive answer. Joe Bryant’s landmark “Value Base Drafting” system explained that the “value of a player is determined not by the number of points he scores, but by how much he outscores his peers at his particular position.” Bryant came up with the concept of calculating a ‘VBD’ number for each player to measure their value.

A player’s VBD is easy to calculate. Each player’s VBD score is the difference between the amount of fantasy points he scored and the fantasy points scored by the worst starter (at his position) in your fantasy league. A player who scores fewer fantasy points than the worst starter has a VBD of 0. There is no standard scoring system for fantasy leagues, so a player’s fantasy points total will depend on the specific league’s scoring rules. And, of course, his VBD score will change depending on the number of starters at each position in the league.

That said, once you pick a scoring system and a set of rules, it’s easy to calculate career VBD scores for every player since 1950 . Let’s start with the quarterbacks:

[continue reading…]

Tagged as:

Don Maynard,

Emmitt Smith,

Jerry Rice,

Jim Brown,

LaDainian Tomlinson,

Marshall Faulk,

Priest Holmes

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on August 20, 2012

New England has had one of the most creative and flexible offenses for the last decade. From 2002 to 2011, the Patriots offense was always good but it was rarely predictable. On paper, the Patriots arguably have their best and deepest set of skill position players in franchise history. But with the addition of Brandon Lloyd to a group that includes Wes Welker, Rob Gronkowski and Aaron Hernandez, many are wondering what the breakdown will be in the passing game in 2012. Let’s not forget that Tom Brady passed for the second most yards in NFL history last year and then the team signed Josh McDaniels’ favorite Brandon Lloyd.

Before speculating on the 2012 season, we need to look at how the Patriots passing game has operated in the past. The chart below shows a breakdown of targets in the New England passing game for each of the past ten years by position:

Some thoughts:

-

Kevin Faulk used to get around 55 targets per season, but New England has essentially fazed the running back out of the passing game. I doubt that is by design, but more a reflection of New England’s failure to find the right replacement at the position. Note that New England signed ex-Florida Gator running back and Olympic silver medalist Jeff Demps last week, although he is unlikely to make an immediate impact.

- From ’02 to ’05, the Patriots had a pretty consistent offense. Troy Brown, David Patten, Deion Branch, and David Givens each spent time as the main receiver, and in ’02, ’04 and ’05, wide receivers as a group saw 63-64% of the Patriots’ targets. In ’03, Brown had fallen off while Givens and Patten weren’t main cogs in the offense, but otherwise, New England’s offensive philosophy didn’t vary. Then, after the 2005 season, the Patriots traded Deion Branch, who had seen 23% of the team’s targets in that season. The ’06 Patriots responded by throwing more to Ben Watson, which ultimately proved not to be the answer.

- In 2006, Reche Caldwell led the team in targets, which prompted the Patriots to add Randy Moss and Wes Welker in the following off-season. Whereas the targets for the WR1 and WR2 had been declining from ’04 to ’06, in 2007, Moss and Welker received over 50% of the team’s targets, and the tight ends and running backs became less integral. In 2008, even without Brady, little changed with Matt Cassel running the offense, with the most notable decline being the lack of targets for the fourth, fifth and sixth wide receivers. 2009 resembled 2007, as Brady got the Sam Aikens and Joey Galloways of the world involved. By that time, the Patriots were running a full spread offense, and had almost entirely forgotten about the tight end. But much of that was out of necessity: Ben Watson was in his final year with the team and the Patriots wanted more speed on the field; New England had signed Chris Baker to be the backup tight end, but the long-time Jet had little left in his tank.

- In that context, perhaps it isn’t surprising that New England added Rob Gronkowski and Aaron Hernandez in the 2010 draft. Moss had worn out his welcome, and New England struggled to find a true replacement. The Patriots turned to their young tight ends, along with Danny Woodhead, but still were weak at wide receiver as Brandon Tate and Julian Edelman were not competent as backup wide receivers. In the off-season, the Patriots signed Chad Ochocinco, which turned out to be a disaster. Outside of the WR1 and WR2, the other wide receivers and the running backs averaged 39% of the team’s targets from ’02 to ’10; in 2011, that number dropped to 18%, the first time that group failed to have at least 31% of the team’s targets. In ’03, for example, the backup WRs and the RBs had nearly 50% of the targets, but the talent was there: David Givens, Bethel Johnson, David Patten, Kevin Faulk, Larry Centers and Antowain Smith weren’t stars, but were competent in their roles. Last year, Ochocinco, Edelman and Tiquan Underwood added almost nothing, while only Woodhead was a threat in the passing game among the running backs.

So what can we expect for 2011? BenJarvus Green-Ellis is gone, but New England doesn’t seem likely to give Shane Vereen many more targets. I think we can safely conclude that the Patriots won’t be depending on their running backs to gain yards through the air in 2012. But I do think the Patriots want more from their wide receivers, and the signing of Brandon Lloyd should increase the production of both the WR2 and the WR3, which is where Branch will now be. Assuming he isn’t cut, I doubt Branch is fazed out completely — Ochocinco saw only 5% of the Patriots targets last year, but usually New England will target their third wide receiver around 10% of the time. With so many mouths to feed, Welker is likely to see a small decline in attention. If we put Welker at 23%, Lloyd at 19%, Branch at 9% and the other wide receivers at 3%, that would mean Brady would target his receivers on 54% of his passes. Giving the running backs 10% — the same number as last season — would leave 36% for the tight ends. We’ll probably see both Gronkowski and Hernandez each up with 18% of the targets, as Brady hasn’t shown a significant preference for either player.

Assuming strong production per target, it’s certainly possible for Welker, Gronkowski and Hernandez to all have monster years in 2011 *and* for Brandon Lloyd to improve on Branch’s numbers and for Branch to improve on Ochocinco’s performance. Of course, all of this assumes — or signals — that Tom Brady is going to have a monster year if things go according to plan. But to expect Brady to improve on last year’s numbers may be asking too much.

For fantasy purposes, the bigger question might be about the size of the pie rather than about its breakdown. If New England’s defense is better, the Patriots could certainly end up passing less this year. Brady may be more effective per pass, and could put up lofty touchdown numbers, but without a high number of attempts (aided by a bad defense) it’s unlikely we see Brady set his sights on 5,000 yards again. I think the Patriots offense can handle the addition of Brandon Lloyd, and think it’s clear that Belichick wants to incorporate that vertical threat on the outside into his offense. And let’s not forget, the offensive line is as unsettled as it’s been in years. From a fantasy perspective, though, it will be important not to chase last year’s numbers too much.

If Welker and Gronkowski each lose 10% of their targets, and then the Patriots also throw 5% less frequently, those small slices can add up. Welker with 100 catches is a lot less valuable than Welker with 122 catches. I don’t think any of the stars in New England bust, but if that defense can approach league average levels, all of the Patriots stars may end up failing to live up to their fantasy draft status. I suspect that Brady finds the open receiver and doesn’t lock on any of his targets, leaving Gronkowski, Welker, Lloyd and Hernandez with very similar receiving yards totals. Gronkowski should lead in touchdowns and Welker in receptions, but otherwise good luck predicting which player Brady will lock in on in any given week. One mark that could possibly fall: New England might be the first team to have four 1,000-yard receivers in the same season.

Tagged as:

Aaron Hernandez,

AFC East,

Bill Belichick,

Brandon Lloyd,

Josh McDaniels,

Patriots,

Rob Gronkowski,

RPO 2012,

Wes Welker

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on August 15, 2012

McFadden begs you not to touch him.

has missed games due to injury in each of his four seasons in the NFL. But he earns the label “injury prone” instead of “bust” thanks to his incredible production the past two years. In 2010 and 2011, McFadden totaled 2,432 yards from scrimmage and 15 touchdowns in 20 games while averaging 5.3 yards per carry and 10.0 yards per reception.

But is the injury prone label fair? From a rearview standpoint, it certainly is. But the label carries with it the perception that he will continue to be injury prone. Is that fair?

From a statistical standpoint, we’re really limited by sample size. In the past two decades, only a handful of young running backs have been as productive as McFadden despite dealing with significant injury issues. Ricky Williams played in 12 and 10 games his first two seasons, and earned the injury prone label before three straight 16-game seasons. Steven Jackson missed games here and there early in his career, and in fact still has just two 16-game seasons in his career. But Jackson is no longer considered injury prone and has also registered three 15-game seasons.

Fred Taylor resided for years at the intersection of talented and injury prone, earning colorful nicknames like ‘Fragile Fred’ and ‘Fraud Taylor.” He played in only 40 games in his first four seasons, but still scored 37 touchdowns, averaged 4.7 yards per carry, and averaged 106 yards from scrimmage per game. He would play in 16 games each of the next two seasons, before missing games due to injury every other season for the rest of his career.

Cadillac Williams played in 14 games in each of his first two seasons, and things only got worse from there. He played in just 10 games the next two seasons, before playing in 16 games in both 2009 and 2010. Julius Jones missed significant time in each of his first two seasons, but then played in 16 games in each of his next two years. On the other hand, Kevin Jones’s career went 15-13-12-13-11 in terms of games played. Robert Smith was a track star on the gridiron and often seemed as tough as one. In his first two seasons as the starter with the Vikings, he wound up being inactive half of the time each year. In 1997 and 1998, he played in 14 games, but Smith would only play one 16-game season in the NFL: his last one.

But back to McFadden. Let’s start with some baseline about what the anti-McFadden would look like. From 1990 to 2010, there were 91 running backs, age 25 or younger, who rushed for at least 1,000 yards and played in 16 games. Only 38 of those 91 running backs (42%) played in 16 games the next season, while the group averaged 13.9 games played in the following year. The median was 15 games played, with 58% of running backs playing in 15 or 16 games.

[continue reading…]

Tagged as:

AFC West,

Darren McFadden,

Raiders,

RPO 2012

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on July 2, 2012

Frank Gore is 29 years old and has been the featured back of the 49ers since 2006. Steven Jackson turns the same age in three weeks, and has been beaten and bruised while playing on bad teams his whole career. Michael Turner had his 30th birthday in February, and has accumulated 300 carries in three of the last four years. Fred Jackson (31) and Willis McGahee (31 in October) have had varying degrees of wear and tear during their careers, and are both competing with younger backs on their roster.

We know the wheels will fall off for these players. But do we know when? And how severe the drop-off will be? Each running back is unique, with his own genetics, history, and supporting cast. It’s difficult to find true comparisons to any one running back, let alone a group of runners. Still, we can try to identify the general aging pattern of top tier running backs.

I looked at all running backs who entered the league in 1990 or later, rushed for at least 5,000 rushing yards, averaged at least 40 rushing yards per game for their careers, and are retired. There were 36 such running backs.

Now we need a metric to measure running back productivity. Generally, I don’t think people worry about running backs failing to be factors in the passing game as they age; Kevin Faulk set a career high in receiving yards at age 32. I don’t think the focus is on touchdown production, either, and we all remember Jerome Bettis still being a short-yardage force even when he was well past his prime. No, when people discuss running backs hitting a wall and deteriorating, the focus is on declining rushing yards and rushing yards per carry. One metric I’ve used before is called “Rushing Yards Over 2.0 Yards Per Carry” or RYO2.0, for short. As the name implies, a running back gets credit for his yards gained over 2.0 yards per carry, so 300 carries for 1000 yards is worth 400 marginal yards, as is 1,060 yards on 330 carries. Essentially, we’re looking at just rushing yards with a small adjustment depending on the player’s yards per carry average.

I calculated the RYO2.0 for each of the 36 running backs at ages 22 through 34. The red line represents the average RYO2.0 for the group at each age for all 36 backs; the green line represents the average RYO2.0 only for those backs who were active in the league at that age.

Running Back production by age

Tagged as:

Eddie George,

Emmitt Smith,

Priest Holmes,

Shaun Alexander,

Tiki Barber,

Warrick Dunn

{ }

by Chase Stuart

on June 28, 2012

[Five years ago, my friend and Pro-Football-Reference.com founder Doug Drinen wrote the predecessor to todaay’s article, but refused to go with this title. The principles remain fundamental to advanced analysis of any sport, so today I’ll be revisiting them with current examples.]

Our brains are really good at making connections and finding patterns. In The Believing Brain, Michael Shermer argued that we’ve made it to where we are today precisely because of our ability to do just that:

A human ancestor hears a rustle in the grass. Is it the wind or a lion? If he assumes it’s the wind and the rustling turns out to be a lion, then he’s not an ancestor anymore. Since early man had only a split second to make such decisions, Mr. Shermer says, we are descendants of ancestors whose “default position is to assume that all patterns are real; that is, assume that all rustles in the grass are dangerous predators and not the wind.”

Reggie Wayne dominates when seeing blue.

Of course,

not all patterns are real, and sometimes that rustle is just the sound of the wind. Just because you see a surprising split — maybe a player dominated the second half of the season after a slow start — doesn’t mean that the “trend” is real. For example, here are some splits from the 2011 season:

Reggie Wayne was much better against teams that wear the color blue than when facing teams that have no blue in their uniforms. Here is his weekly production (the last column represents his fantasy points) when playing against teams that do not have blue as a color in their uniform:

| Week | Opp | Rec | Yd | TD | FP |

| 17 | jax | 8 | 73 | 0 | 15.3 |

| 5 | kan | 4 | 77 | 0 | 11.7 |

| 6 | cin | 5 | 58 | 0 | 10.8 |

| 2 | cle | 4 | 66 | 0 | 10.6 |

| 4 | tam | 4 | 59 | 0 | 9.9 |

| 14 | rav | 4 | 41 | 0 | 8.1 |

| 9 | atl | 4 | 30 | 0 | 7.0 |

| 7 | nor | 3 | 36 | 0 | 6.6 |

| 3 | pit | 3 | 24 | 0 | 5.4 |

| 10 | jax | 3 | 13 | 0 | 4.3 |

| Avg | | 4.2 | 47.7 | 0 | 9.0 |

[continue reading…]

{ }